PRIZREN — There are some cities in other countries that somehow seem so familiar that you almost feel like you are at home; it is the language you hear, the many familiar words you catch here and there on shop and street signs, and a song which you can easily sing along to.

Sometimes the streets, the buildings and maybe the faces of the people make the air you breathe magical, just like in Prizren. From the moment you first set foot in Prizren you feel like you are in an Anatolian city such as Bursa, a typical Ottoman city.

But in Prizren it feels more Ottoman as time has been virtually frozen since 1455. Prizren is the second biggest city of Kosovo and as a settlement it dates back to ancient times.

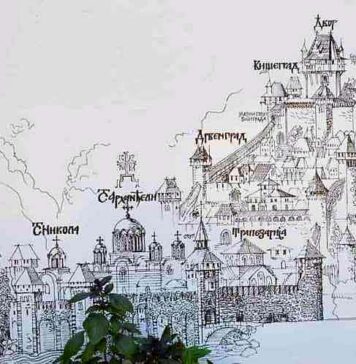

It was established in a convenient location as an important trading town where old roads passed toward the Adriatic coast and the interior of the Balkan Peninsula. Many civilizations, including the Roman and Byzantine, settled in Prizren throughout history but the Ottoman Empire was the most influential empire to rule there for 550 years. In the era of Roman rule it was called Theranda. After the Romans, under Byzantine dominance, it was referred to as Prizdrijana. When Fatih Sultan Mehmet conquered the town in 1455 it was avowed as Purzerin, which means „full of jewelry.“ The city’s long tradition of religious and ethnic tolerance stemming from the Ottoman notion of „la convivencia,“ which means „the art of living together,“ is still apparent in the close proximity of the city’s mosques, dervish lodges and Catholic and Orthodox churches. Today Prizren is a true open-air museum.

It is located on the slopes of the Sharr Mountains and on the banks of the Bistrica River. Thanks to its well-preserved architecture, the town is rich in historical structures. An old stone bridge that serves as Prizren’s landmark was built by the Ottomans in the first half of the 16th century and touches the two shores of the Bistrica River. In 1979, heavy floods washed the bridge away but it was renovated in 1982.

Şadırvan is the name of the city center, a word meaning „fountain with many streams.“ There is a small fountain in the middle of the square which interlaces oriental and western styles of architecture. The square is located at the center of a mosque and two churches.

When the Ottomans first arrived in Prizren, a commander of Fatih Sultan Mehmet named Isa bey built a namazgah (open-air mosque) in a very short time so worshippers could partake in common prayers together. It was the first cultural Islamic monument in the city. Restoration work on the mosque was done by the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TİKA) in 2010. There are more than 20 mosques in the city. One of the most important is the Mosque of Sinan Pasha. It was built in 1615 by Sofi Sinan Pasha, the Ottoman Governor of Bosnia. The mosque overlooks the main street of Prizren and is a dominant feature of the town’s skyline with its huge dome and elegant minarets. A madrasa and a library once belonged to it too.

The mosque has a square plan and the dome apex is decorated with colored paintings in different motifs encircling a Qur’an verse. It is very rich in ornaments of many colors and shapes with flora and fauna decorated in the baroque style. During World War I, parts of the mosque were damaged. The mosque was restored by TİKA and has a capacity of 800 people for prayers. The sermons are still held in Turkish and last year Necdet Özel, the Turkish chief of general staff, visited the mosque. „May you have a large congregation,“ wrote Özel when he signed the mosque’s guest book. Beside the mosques, there are some dervish lodges in Prizren, which have been around since Ottoman rule, such as Melami, Halvet, Bektashi, Saadi,Kadiri and RufaiTekkes. Another important monument and one of the oldest buildings to hold the rich history of the city is St. Friday’s Church, also known as Juma Mosque. The building was actually a pagan temple over which a Roman Catholic basilica was built. A Byzantine basilica was then constructed on the remains of the Roman chapel and in 1306 expanded by King Milutin into the Nemanjic Orthodox Cathedral. In 1455 with Fatih Sultan Mehmet’s conquest of the town, the great Ottoman sultan performed his Friday prayers in this Orthodox cathedral and it was consequently converted into a mosque. In 1912 after the Serbian invasion, it was turned back into a Serbian Orthodox church. The Church of St. George is another prominent monument in the city center with an interior that was once elaborately decorated with ashlar stones and marble panes. The Cathedral of the Catholic Church is another historical monument. It has played a central role in the Roman Catholic Church in the Balkans.

It was built in 1871 on the foundations of an age-old church and is dedicated to the Holy Virgin.

Prizren is dotted with Ottoman works of architecture in almost every corner of the city, including houses. They were mostly built with two floors and big gardens and fountains.

In Prizren, a house with big doors suggests that the house belongs to rich people or local notables.

Albanians make up the majority of the city, with the addition of Turks and Serbians. People speak Albanian, Turkish and Serbian and even municipal signs are written in all three languages. Almost everyone in Prizren can understand and speak Turkish. The city’s older people claim that if there are people who can’t speak Turkish then they are probably çövli-köylü (villagers). The Turkish accent here sounds like that of people from Trabzon and Rize of the Black Sea region.

Yunus Emre Cultural Center in Prizren was founded by the Turkish government and hosts special Turkish language courses and even poetry readings. For the people of Prizren, literature and poetry still holds much importance. Ottomans used to describe Prizren as the „home of the poets.“

Turkish national poet Mehmet Akif Ersoy was born in a village nearby Prizren. Prizren has many more attractive features to describe here, but it would be best to see them for yourself. After walking the streets and drinking some tea in a traditional café by the river nearby Sinan Paşa Mosque, you will breathe the history of a real Ottoman city and I assure you it will feel like home.